It’s a beautiful world.

The British Geological Survey’s 3D mapping shows us the world in a new light.

For such intensely practical publications British Geologic Survey maps have an extraordinary beauty. Finely detailed, colourful, exquisitely printed, they endeavour to show the complex geological structures and formations that make up the planet we live on. They have been revered as pinnacles of the mapmaker’s art since 1835.

From prospecting to prediction

Yet despite their beauty and precision they have one inherent and inescapable flaw. They must show a three-dimensional world in two dimensions. And it’s hard not to over-state just what a problem this can be. Geological mapping is used to calculate earthquake probabilities, to predict floods and to inform flood defences. It has turned the search for valuable minerals from a lottery of prospecting to one of near-certain predictions and moved our understanding of life on earth forward through an increasingly complete fossil record. Scientists at BGS produced the first comprehensive map of African groundwater reserves.

But to use even the best maps every geologist and surveyor and amateur fossil-hunter must learn the trick of turning a two-dimensional paper image into a three-dimensional mental picture, something that’s neither easy nor reliably repeatable. It’s why one of BGS’ key aims for the next decade is to complete a move from 2D mapping to 3D imagery.

A wholesale move to 3D mapping

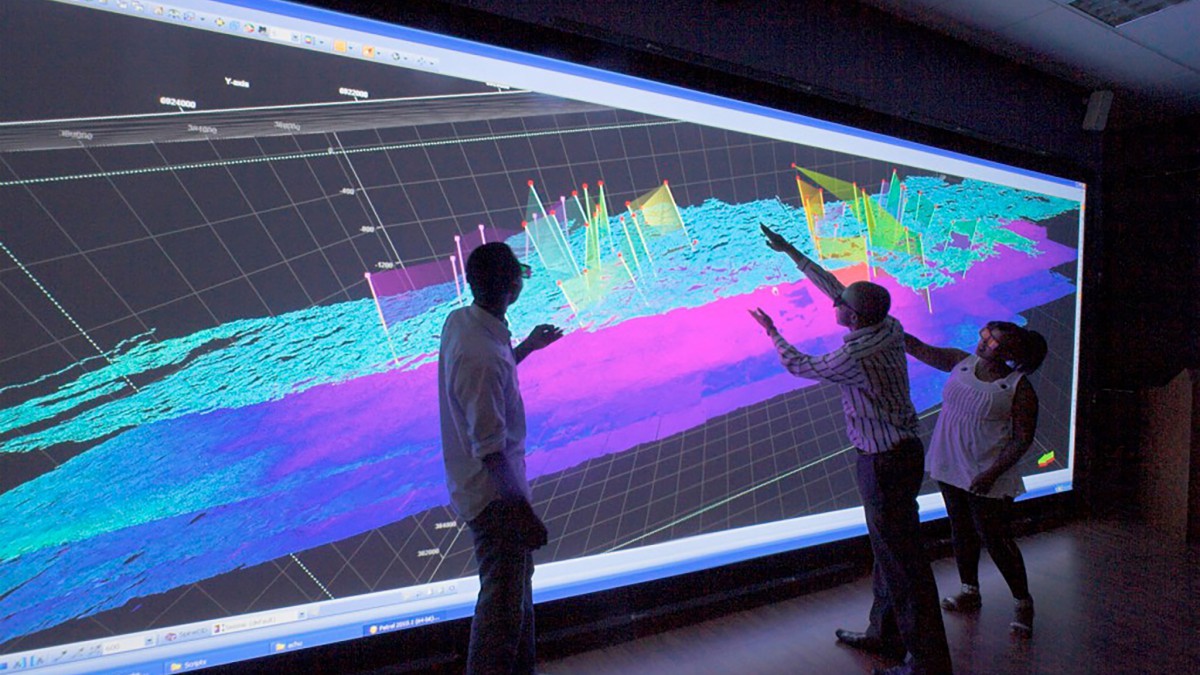

Little wonder Virtalis, one of the world’s leading exponents of VR in industry have found such enthusiasm for their StereoWorks visualization system among the British Geological Survey – as Doctor Martin Smith, Head of Station, BGS, Edinburgh, explains: “With VR the need to move from 3D to 2D and back again is negated. A project team can work together to construct a 3D model, interact with the data and interpret them as a group.”

Early enthusiasts for Christie’s Mirage S+4K projector, Virtalis had used it as part of an integrated StereoWorks visualization at BGS headquarters in Nottingham and then in an almost identical installation at a regional facility in Edinburgh. So successful were these that Virtalis proposed an upgrade to a full 3D immersive modelling environment.

This demanded a Virtalis-written software package — and the Christie Mirage S+4K’s ability to project high-grade active stereo onto a 3.1 x 2.3m screen.

An immersive and collaborative experience

Andrew Connell Virtalis technical director says Christie’s Mirage has a lot going for it in this 3D environment “This tool allows geologist to present their findings in a compelling and involving way. It supports head and hand tracking for a fully immersive stereo display.” The Mirage’s input bandwidth of 220MHz means the image can also react instantly to the user’s head position and provide a holographic effect – and then geologists become genuinely immersed in the landscape.

Able to read data from models including strata, earthquake epicentre and magnitude, geo-specific imagery and conventional data, multiple images can be blended onto the same underlying topography. Satellite imagery can merge with political maps – and then fade into color-coded geological data.

Mental gymnastics

All of this can be presented in a twenty-seat theatre; however, Dr Stuart Clarke, the survey geologist at BGS responsible for developing many of the 3D models, says it works most powerfully when teams of five or six can get close to the high resolution images and ‘take full advantage of the 3D stereo effect by becoming totally immersed. Prior to this we were spinning models onscreen; but 3D images on a flat screen can often mislead — there is a potential for the brain to misinterpret because of the way visualization plays tricks. Stereo gives us a way of visualizing these models with a correct perspective.’

It’s this ability to put teams inside their subject as virtual participants rather than observers that makes 3D such a ground-breaking technique – and that’s only possible because the high-resolution images create a believable and truthful experience.

The British Geological Survey, Virtalis and Christie are helping scientists look at the world in a different way – one that will have a profound effect on the understanding of how our home planet works, the resources it contains, and the threats it faces as our population grows and climate changes.

Amid all this change, and whilst Geological Mapping may have come a long way since paper and ink, two things remain constant, an undimmed desire to explore the earth in all its complexity, and the undeniable beauty of the images that are created to explain it.